After a dismal year in 1991 and a rocky start to the following season, I, like a lot of Montreal Expos fans, experienced a renewal of my love for the team and for baseball itself in 1992. Behind this renaissance was (at the time, interim) manager Felipe Alou, who replaced the fired Tommy Runnells on May 22 when the team was 17-20 and stood five games behind the National League East-leading Pittsburgh Pirates. Under Alou’s aggressive and exciting style of managing, a roster stocked with promising yet inexperienced young players treated us all to an unexpected and thrilling pennant race that year.

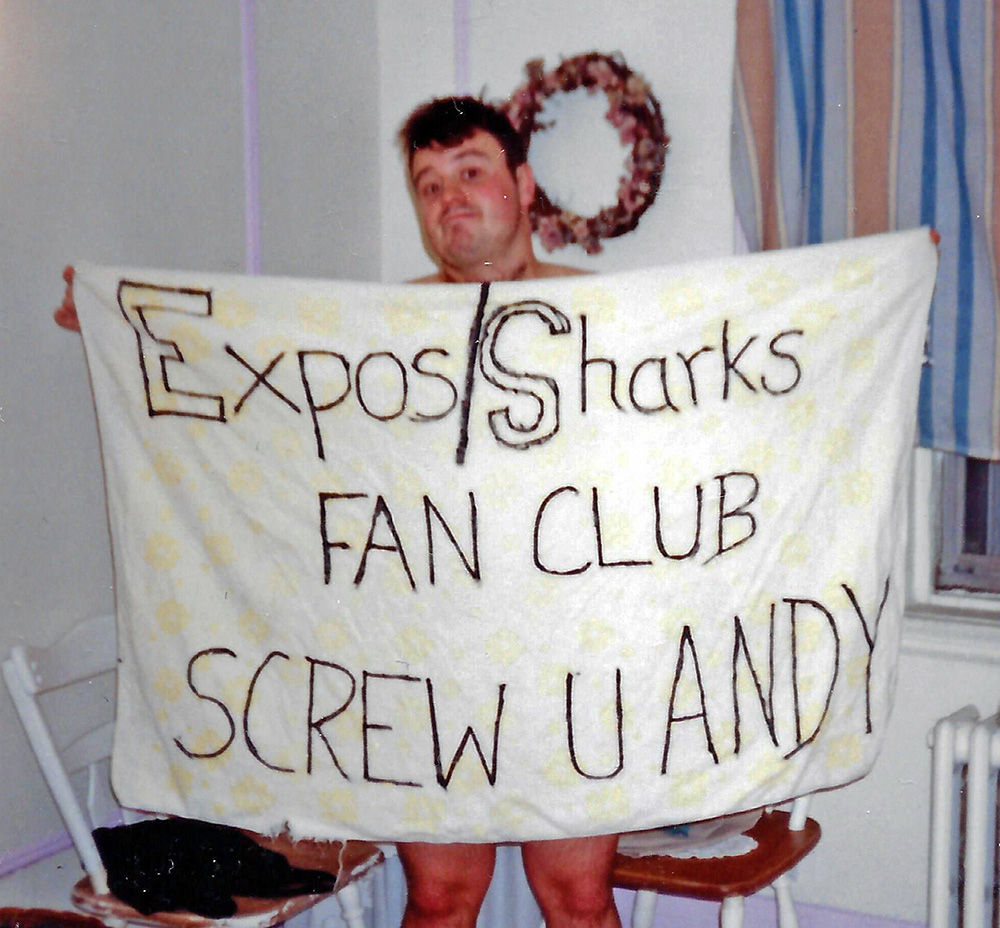

On September 23, the Pirates came to Montreal for the first of a two-game series at Olympic Stadium. By this time, the Expos were 13 games over .500, but trailed Pittsburgh by seven games with only 11 left to play in the season. Montreal was all but mathematically eliminated, but I, along with my friends Dickles, Knot, and Truehell, plus my little brother Nic, were fired up to attend the game. Not only did we have the Expos to look forward to cheering for, but we also really wanted to give it to Pirates’ centerfielder Andy Van Slyke, who had recently disparaged Montreal baseball fans by suggesting we knew more about the San Jose Sharks hockey team than we did about the Expos. In honour of Van Slyke, we fashioned a large sign from an old yellow bedsheet that said EXPOS/SHARKS FAN CLUB – SCREW U ANDY and even brought along a San Jose Sharks flag that young Nic had received for his birthday that year. As Van Slyke stepped to the plate in the first inning, the Olympic Stadium public address team added to the fun by playing a few bars from Dionne Warwick’s “Do You Know the Way to San Jose.” When Expos’ ace Dennis Martinez struck him out looking to end the inning, we, along with 30,000-plus Expos fans, cheered with no shortage of zeal and glee.

Our seats were just a couple of rows up from the playing surface, in the deepest part of right field that you could get to at that time (this was the last season before the “home run bleachers” were installed behind the outfield fence at Olympic Stadium). Martinez threw a real gem that night: nine innings of work, allowing no runs, only two hits, one walk, and striking out six. Unfortunately for him, the game was scoreless after nine innings of play. Fortunately for us, this set up one of the most exciting extra-innings sessions I have ever witnessed.

Martinez was replaced on the mound in the tenth inning by Felipe Alou’s nephew Mel Rojas. Barry Bonds singled to lead off the top of the inning for Pittsburgh, was promptly sacrificed to second, and then moved to third on a groundout. Don Slaught’s two-out single scored Bonds, and the Expos were down 1-0, in need of at least one run when they came to the plate in the bottom of the inning.

Moises Alou, the manager’s son, started things off by doubling down the third base line. After Tim Wallach flew out, Bret Barbarie grounded out to move Alou to third base. Down to his last out, Felipe Alou opted to pinch-hit for catcher Tim Laker, who had entered the game in the tenth inning to replace future Hall of Famer Gary Carter behind the plate. Alou’s unconventional partiality to carrying three catchers on the roster allowed him this luxury, and it paid off in spades when John Vander Wal doubled to score Alou and tie the game. In the stands, we were delirious. And even though Darrin Fletcher, the third Expos’ catcher to take the field that night, pinch-hitting for Rojas, failed to extend the inning, our joyous mood did not let up.

Cecil Espy entered the game as a pinch-hitter for the Pirates to lead off the top of the 11th. He would go on to strike out, as did Pittsburgh’s next two batters, victims of closer John Wetteland’s blistering fastball. Espy assumed the right field position in the bottom of the inning, not far from our seats, and we heckled him mercilessly throughout the remainder of the game. Our voices already hoarse, we mock-chanted his name. Then we asked him if we were pronouncing it correctly: Ess-pee or Ess-pie? (It would be helpful at this juncture to note that our group was made up of one twelve-year old child and four twenty-year old man-children.) Then, quite considerately, we inquired about the proper pronunciation of his first name, too: Se-sill, or Ke-kill? A giggling fan sitting nearby told us how funny we were, a fact that we (obviously) were already well-aware of. He then proceeded to yell out, “Hey, Kekill! I want to be your friend!”

After nearly four hours of play, the Expos loaded the bases in the 14th inning. Moises Alou stepped to the plate with the potential winning run on third base and one out. He blasted the first pitch he saw high and deep down the left field line. Alou jogged a few steps toward first base and, with the ball still in the air, stopped, crouching with his hands on his knees, to watch if it would stay fair. When it did, landing in the outstretched hands of a fan standing not far from the left field foul pole, Alou pumped his fist and trotted around all of the bases for a spine-tingling walk-off grand slam home run. The Stadium exploded with thunderous cheers. In our section we were jubilant; my friends, my brother, and I hopped up and down, slapped each other on the shoulders, and embraced. It was the capper on one of the most memorable games I ever attended, near the end of one of the more memorable baseball seasons I ever followed.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.